Samart Payakaroon: Greatest of All Time in Muay Thai?

Among Thailand’s greatest fighters, the debate over the true GOAT always circles back to the muay femurs—the technicians who seemed to float across the canvas from one side of the ring to another, setting traps for their opponents. But within this elite group, there’s an unspoken hierarchy—some names linger longer in memory, not just for their mastery of the art, but for something less tangible. An aura, a presence, a face that belonged on posters as much as it did on fight cards.

Roots (1962-1978)

Samart Payakaroon was born in 1962 in Chachoengsao, Thailand, into a working-class fishing family. His older brother, Manus Thipthamai, was passionate about Muay Thai and introduced Samart to the sport at a young age. Initially, Samart had little interest in fighting, preferring to play with girls rather than engage in rough play with boys. Worried that he was too soft, his brother and neighborhood kids forced him to fight, offering small cash prizes. He had his first official fight at a local temple fair, earning 40 baht, which sparked his interest in the sport.

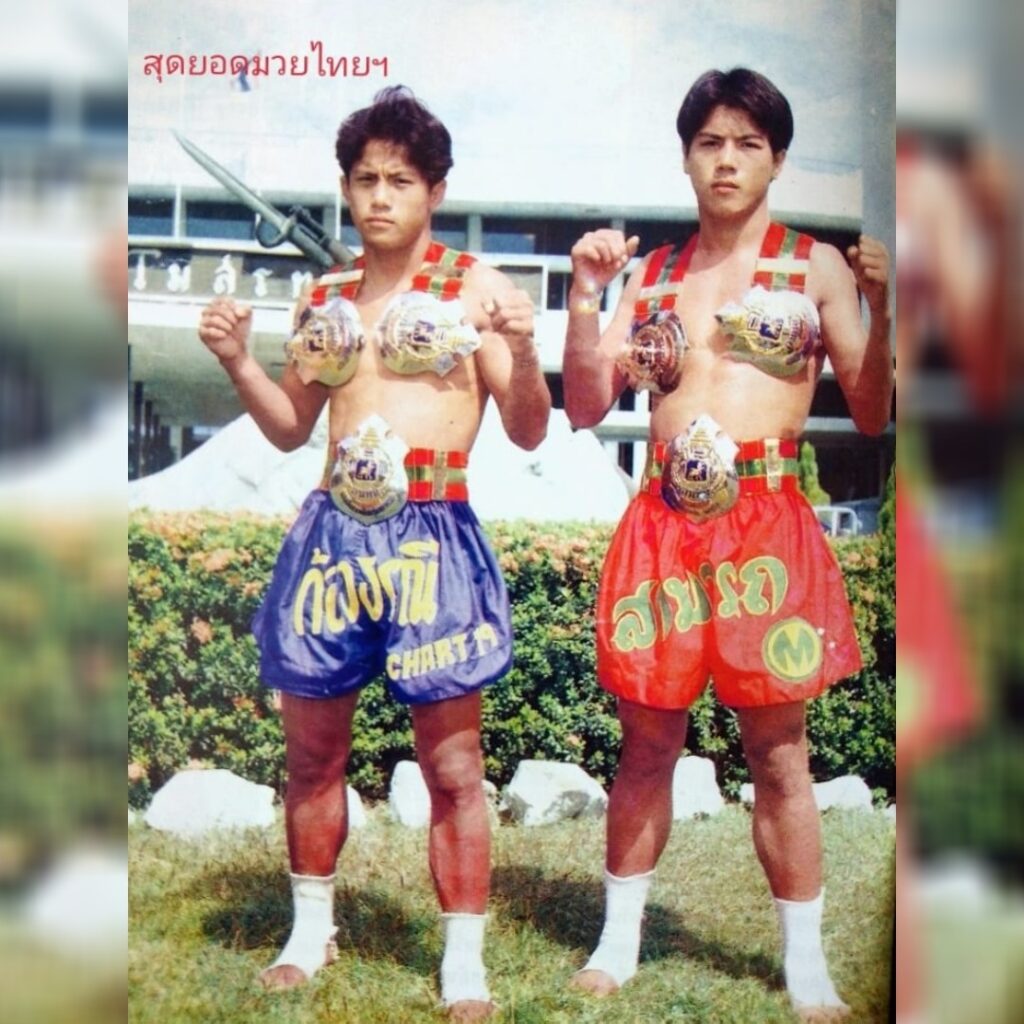

By age 10, he was training seriously and fighting under the name “Samart Lookkongket.” After losing his mother and seeking better opportunities, he left home at age 12 and moved to Pattaya, where he joined Sityodtong Gym under the legendary Yodtong Senanan. Here, he developed a technical, elusive, and highly intelligent style.

By 1978, at age 16, he began fighting at the “Mecca” of Muay Thai – Lumpinee Stadium.

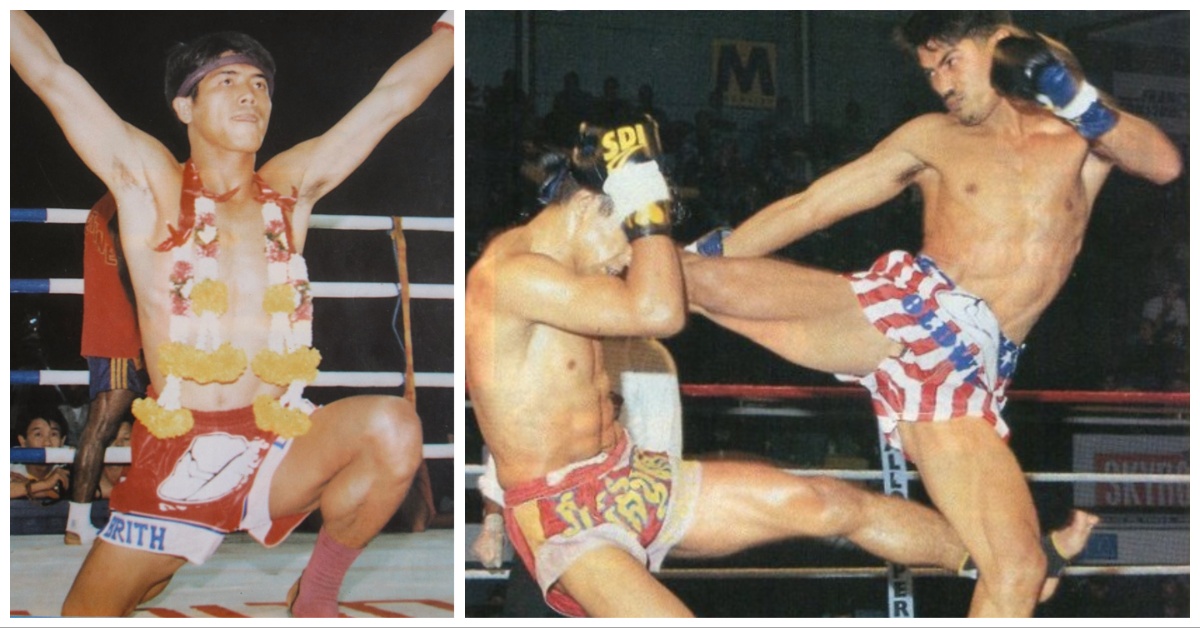

GOAT Status (1979-1984)

In 1979, he endured a three-fight losing streak at Lumpinee Stadium, suffering back-to-back decision losses to Jampatong Na Nontachai before being knocked out in the third round by Paruhatlek Sitchunthong. Jampatong was a former Rajadamnern champion known for neck kick KOs, while Paruhatlek was a future three-weight Lumpinee champion.

Over the next year, Samart set about developing his signature teep-heavy femur style, blending it with a low boxing guard, allowing him to throw from awkward angles and overcome any Muay Thai style. His rivalry with Paruhatlek continued into 1980, with Samart securing two wins, while their fourth fight ended in a draw.

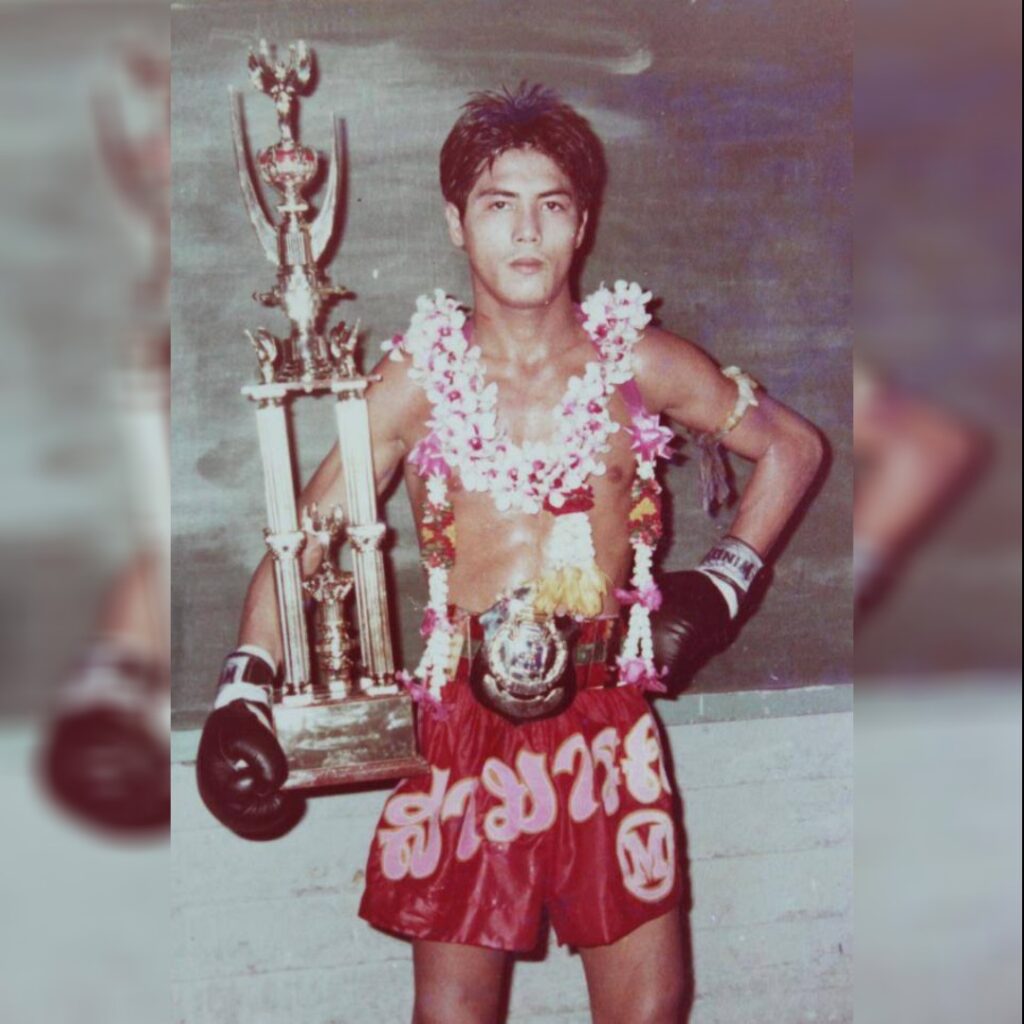

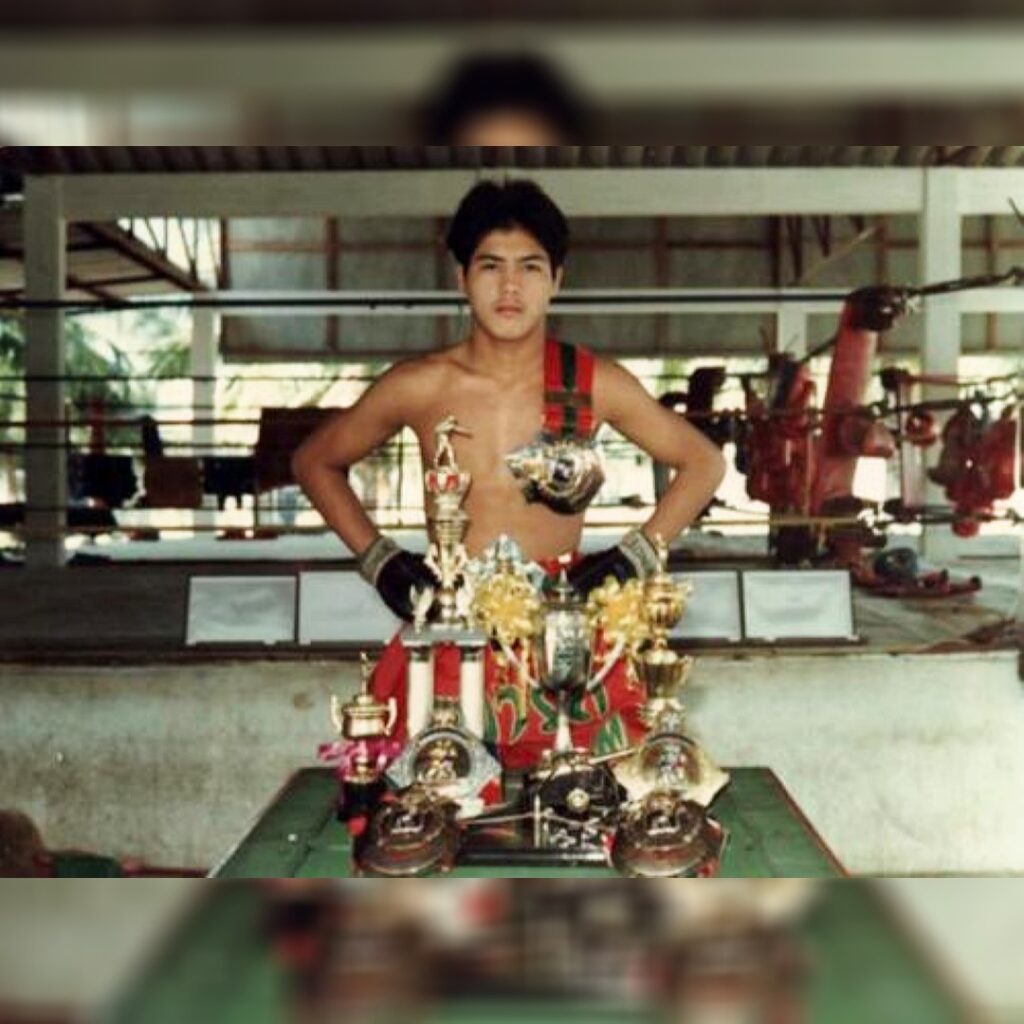

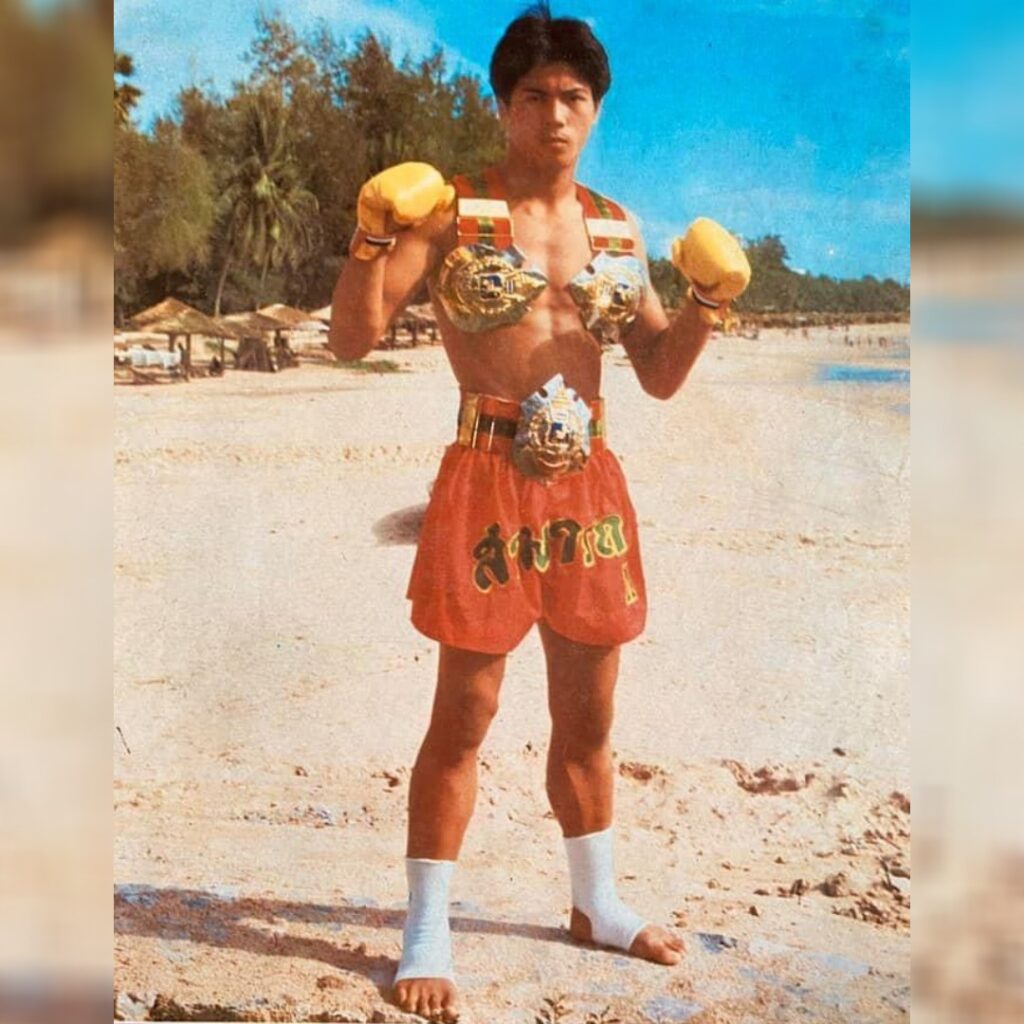

Samart’s breakout year came in 1980, where he fought 12 times, winning 9 bouts, including the Lumpinee Pinweight (102 lbs) title and the Lumpinee Light Flyweight (108 lbs) title. Though he lost the Pinweight title to Chamuekpet Hapalang in August, he avenged the loss in December.

His peak continued in 1981, where he won all seven fights, capturing two more Lumpinee titles—the Super Flyweight (115 lbs) title in March and the Featherweight (126 lbs) title in October.

By this point, he was widely regarded as the best pound-for-pound Muay Thai fighter in Thailand, with his dominance being recognised with the 1981 Sports Writers Association of Thailand Fighter of the Year award. His bouts earned him Fight of the Year honours in 1981 against Mafuang Weerapol and again in 1982 against Dieselnoi Chor Thanasukarn.

In 1983, he reclaimed Fighter of the Year, solidifying his reputation as one of the greatest Muay Thai fighters of all time at the age of 22.

By 1984, Samart had cleared out his divisions. With no real challenges left in Muay Thai, he made the bold decision to transition to professional boxing.

Boxing Transition (1985-1987)

Samart’s natural fight IQ, slick footwork, and counterstriking made him a natural in western boxing. Fighting from a southpaw stance, he built an 11-0 record within two years, earning a shot at the WBC Super Bantamweight (122 lbs) title.

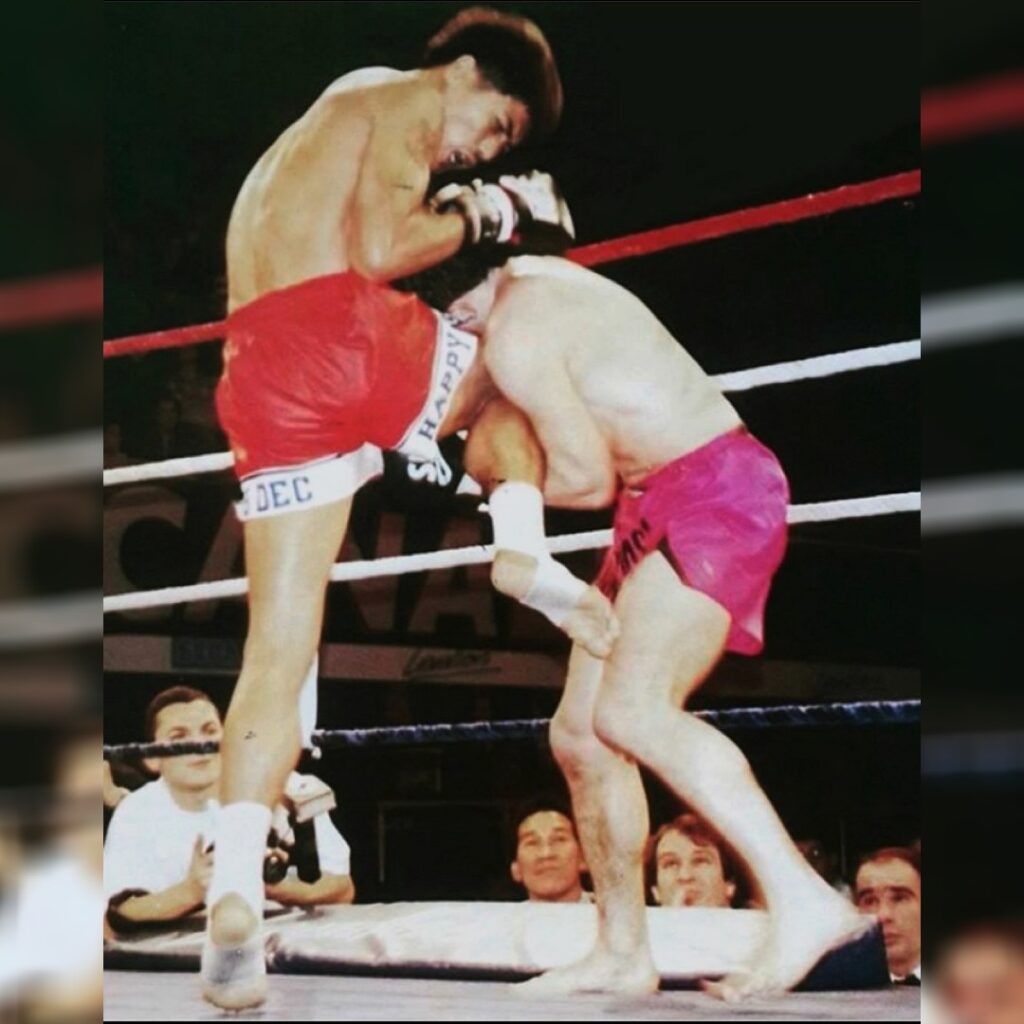

In January 1986, he faced Lupe Pintor in Bangkok. Samart ran rings around the durable Mexican for four rounds before finishing him with a left straight in the fifth.

He followed this with two more wins that year against Rafael Gandarilla and a title defense against Juan Meza, earning The Ring magazine’s Progress of the Year award for 1986.

However, success came at a cost. Fame, wealth, and an expanding entertainment career began pulling him away from training. His discipline slipped, and his preparation suffered. When he travelled to Sydney in October 1987 to defend against Jeff Fenech, he was severely drained from the weight cut. Fenech overwhelmed him, forcing a fourth-round stoppage.

Return to Muay Thai (1988-1993)

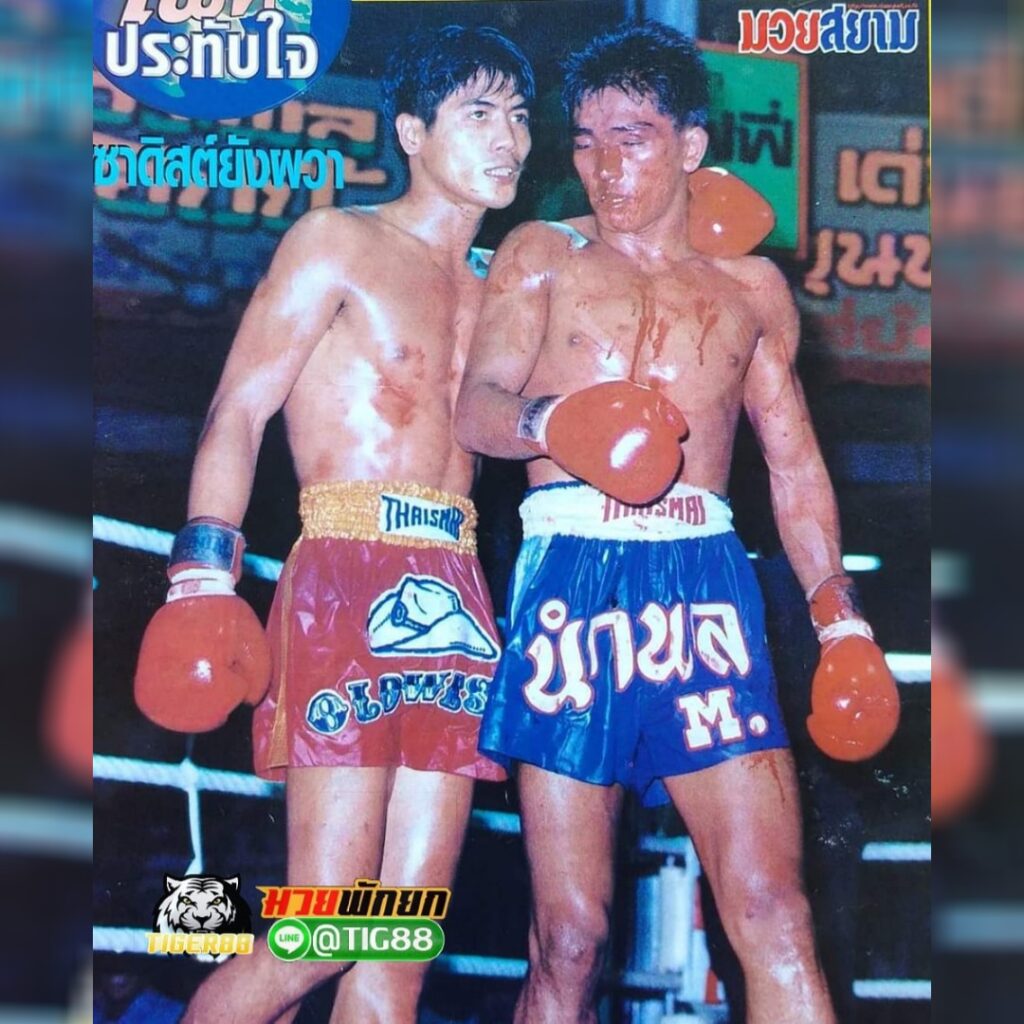

In January 1988, Samart made a stunning return to Lumpinee Stadium, proving that four years out had not dulled his ability. His first fight back was against reigning Lumpinee Super Bantamweight champion Panomtuanlek Hapalang. Despite Panomtuanlek’s pressure, Samart completely dismantled him, softening him up with jabs and teeps before knocking him out with punches in the very first round.

He followed this win by defeating “The Iron Fist” Samransak Muangsurin, the reigning Lumpinee Featherweight champion, twice in a row in May and June.

His resurgence continued as he dispatched the ruthless knee-fighter and former two-time Lumpinee champion Namphon Nongkeepahuyuth in back-to-back bouts in October and December.

He capped off the greatest comeback in Muay Thai history by winning the 1988 Sports Writers Association Fighter of the Year Award, having gone 5-0 with two first-round knockouts and a TKO.

In early 1989, Samart added another elite name to his record, knocking out the reigning Lumpinee Featherweight champion Jaroenthong Kiatbanchong in the first round with a right hook after walking him down and backing him against the ropes.

At this stage, his comeback had seen him walk over some of the best fighters of the era, showing that he still remained a step ahead of the competition even after years away from Muay Thai.

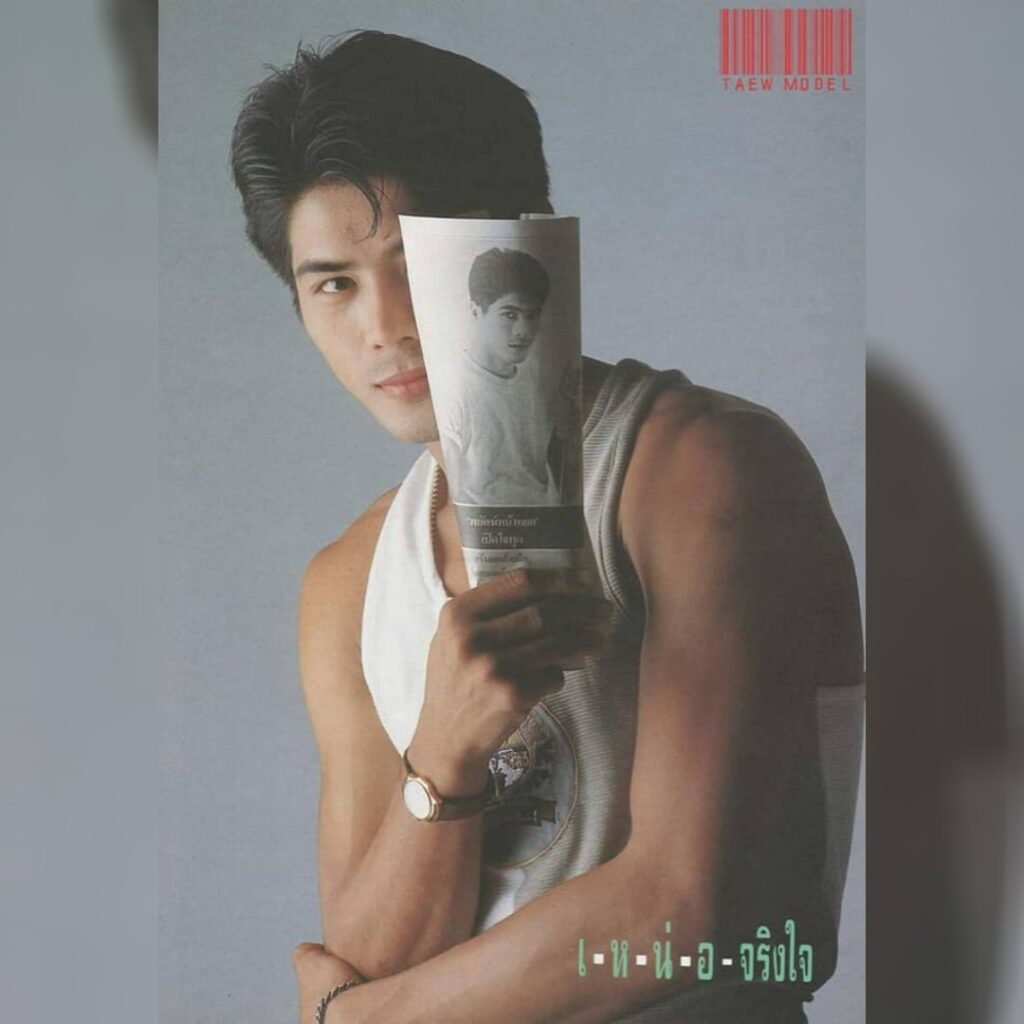

During this time, Samart continued to pursue his entertainment career, becoming a major star in Thailand.

He launched a successful music career, releasing multiple luk thung and luk krung songs, with his debut album becoming a huge hit. Beyond music, he starred in films and TV dramas, gaining a reputation as a charismatic actor.

However, his return to Muay Thai was cut short in May 1989 when he suffered a decision loss to Wangchannoi Sor Palangchai, a fight that would mark his final appearance against a Thai. Samart then stepped away from fighting entirely, shifting his focus to his entertainment career.

Final Stretch

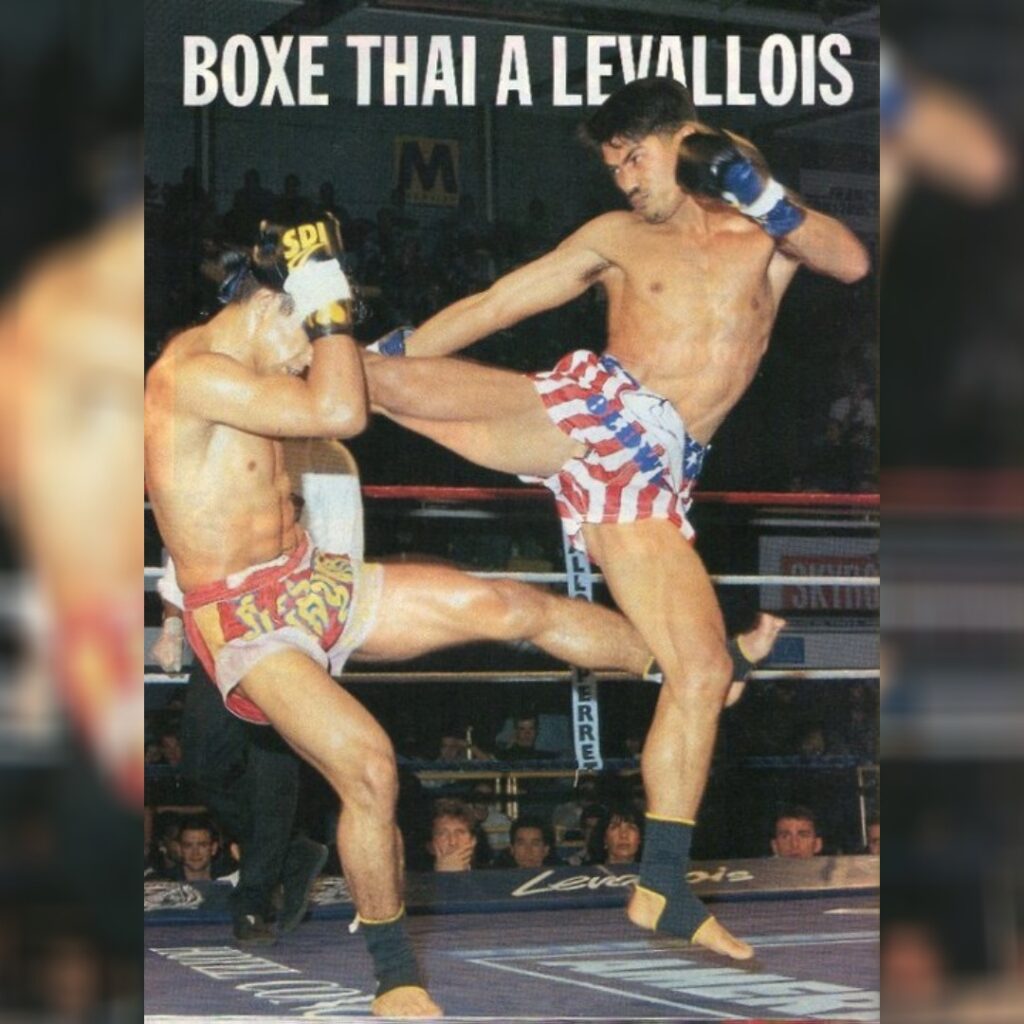

After several years away from competition, in 1993, Samart embarked on an international fighting stint. In October, he faced German fighter Murat Comert in Paris, stopping him with a TKO in the third round.

Just over two months later, he defeated the Dutch “Bull Terrier” Gilbert Ballantine by decision in Bangkok.

Days later, he travelled back to France to take on Ireland’s Paul Lenehan, finishing the fight with a third-round TKO.

He also defeated Japan’s Satoshi Niizuma and Holland’s Maikel Lieuwfat, making a clean sweep of wins on the global stage.

Samart boxed three more times before his final match in May 1994 against Eloy Rojas for the WBA featherweight title, where he lost by TKO in round 5.

Apex of Fight Intelligence?

In Thailand, those who follow Muay Thai closely—especially gamblers and fight analysts—tend to rank femur-style fighters like Pudpadnoi Warrawut, Somrak Khamsing and Oley Kiatoneway more highly than fighters who fought with a more aggressive, power-based approach like Dieselnoi Chor Thanasukarn, Orono Por Muang Ubon or Yodkhunpon Sittraiphum. The fight IQ of the femurs is what makes them truly fascinating, drawing the biggest crowds in Thailand and placing them at the centre of debates about the greatest of all time.

However, Samart’s legacy isn’t just about titles and accolades—it’s about how effortlessly he appeared to achieve them. He seemed to ascend the Lumpinee ranks almost effortlessly, and when he returned to Muay Thai after four years away, he didn’t just compete—he tore through the sport’s golden era elite, totally outclassing two reigning Lumpinee champions with first-round knockouts. His ability to step in and take over at will is what cements him as perhaps the most naturally gifted fighter Muay Thai has ever seen.

Many believe Samart was even better than his recorded achievements suggest. There were periods where he wasn’t fully focused on Muay Thai, whether due to his time in boxing, entertainment, or partying too much. Additionally, many of his prime fights remain unseen. While hundreds of Golden Age fights have surfaced online in recent years thanks to channels like VRX and Steve Armstrong, bouts from the late 1970s and early 1980s remain rare, meaning much of Samart’s early career exists only in records and memory rather than video footage.

For those who witnessed Samart Payakaroon at his best, the debate over the greatest of all time is less of an argument and more of a reminder—some fighters are just different.